It was February when my husband left; the day before Valentine’s to be precise. He walked out and went to another woman. I tried to be positive about it and to get over it as fast as I could. Look on it as an opportunity to change, I said, and what a good thing he left me at this time of year, I said, when we’re moving forward into spring and summer, and not at the onset of winter, when I’d have the dark nights to face.

I spent all the time I could down at the allotment, so that I wouldn’t have to think. I was there early in the morning and stayed until the light went, sometimes later than that. Sometimes in the night when I couldn’t sleep I returned to sit under the stars and nurse my broken heart.

I tried to widen my circle – I joined a gym and wore myself out on the treadmills. I visited friends’ gardens and marvelled at how early everything was coming out.

As the year wore on I thought I was healing and in June I booked a cycling holiday. Wanting to spend time with an old friend in Norfolk, I arranged to join the tour bus there. But once out of my comfort zone, my support system broke down. I went to pieces and couldn’t stop crying. I returned home and cancelled the trip.

In August I was showing some people round the allotment, advising them on what it was possible to grow.

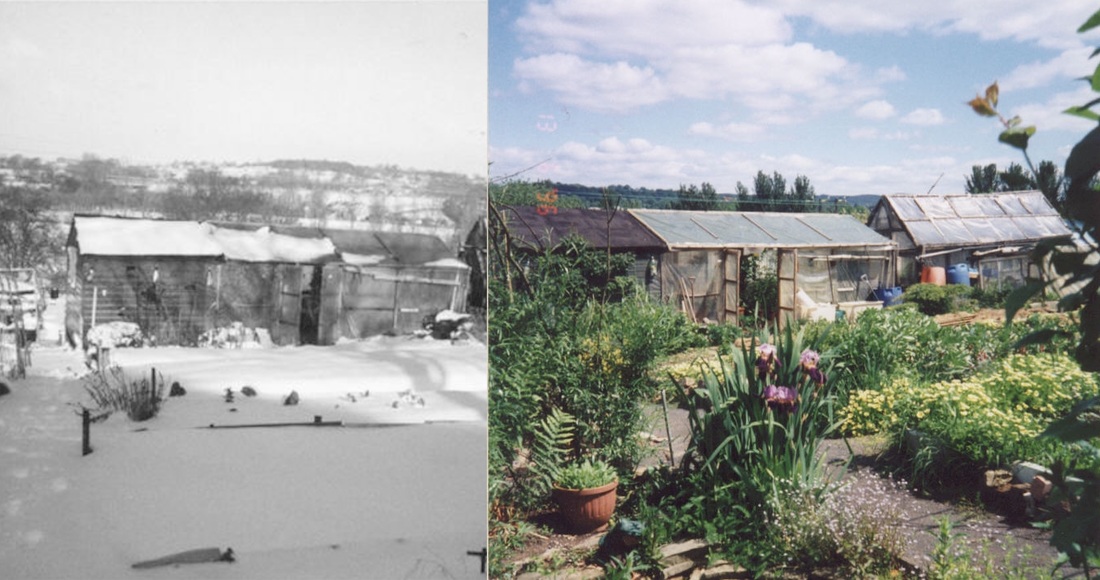

“Of course there’s nothing growing now,” I said, “because it’s winter. But in the summer it’s a different picture.” As I spoke I became aware of something wrong as gradually, imperceptibly, the black, white and grey landscape of February that filled my mind faded away and bright sunlight crept slowly in at the edges of my vision, lighting up the colourful flowers, fruits and vegetables that surrounded us.

What could I say to explain my remark? They would think I was mad. I walked away, leaving them to think what they liked. I knew what it meant. My world had stopped on February 13 when I ended up on an emotional ice floe, far out at sea, separated from the living world.

I spent all the time I could down at the allotment, so that I wouldn’t have to think. I was there early in the morning and stayed until the light went, sometimes later than that. Sometimes in the night when I couldn’t sleep I returned to sit under the stars and nurse my broken heart.

I tried to widen my circle – I joined a gym and wore myself out on the treadmills. I visited friends’ gardens and marvelled at how early everything was coming out.

As the year wore on I thought I was healing and in June I booked a cycling holiday. Wanting to spend time with an old friend in Norfolk, I arranged to join the tour bus there. But once out of my comfort zone, my support system broke down. I went to pieces and couldn’t stop crying. I returned home and cancelled the trip.

In August I was showing some people round the allotment, advising them on what it was possible to grow.

“Of course there’s nothing growing now,” I said, “because it’s winter. But in the summer it’s a different picture.” As I spoke I became aware of something wrong as gradually, imperceptibly, the black, white and grey landscape of February that filled my mind faded away and bright sunlight crept slowly in at the edges of my vision, lighting up the colourful flowers, fruits and vegetables that surrounded us.

What could I say to explain my remark? They would think I was mad. I walked away, leaving them to think what they liked. I knew what it meant. My world had stopped on February 13 when I ended up on an emotional ice floe, far out at sea, separated from the living world.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed